Countless scenarios have been created to determine how humankind will journey into the cosmos. The sources range from the pages of science fiction to the lab reports of college undergrads. Many ideas involve high-tech sleep chambers and robust artificial intelligence systems. But at their very core, each deals with simple questions of survival. How will we build habitats that will function as long as needed? How will we satisfy our basic need to eat, breathe, sleep, and work ?

At a laboratory in Florida, scientists have gotten one step closer to answering that last question. Using samples brought back from previous lunar missions, University of Florida researchers have successfully grown plants in soil (regolith) from the Moon for the first time ever.

University of Florida researchers Anna-Lisa Paul, Stephen M. Elardo, and Robert Ferl planted Arabidopsis thaliana — an oft-studied and genetically mapped species from the mustard greens family— in teaspoon-sized samples of lunar regolith to determine how the plants held up in the foreign soil, according to their 2022 report in Communications Biology.

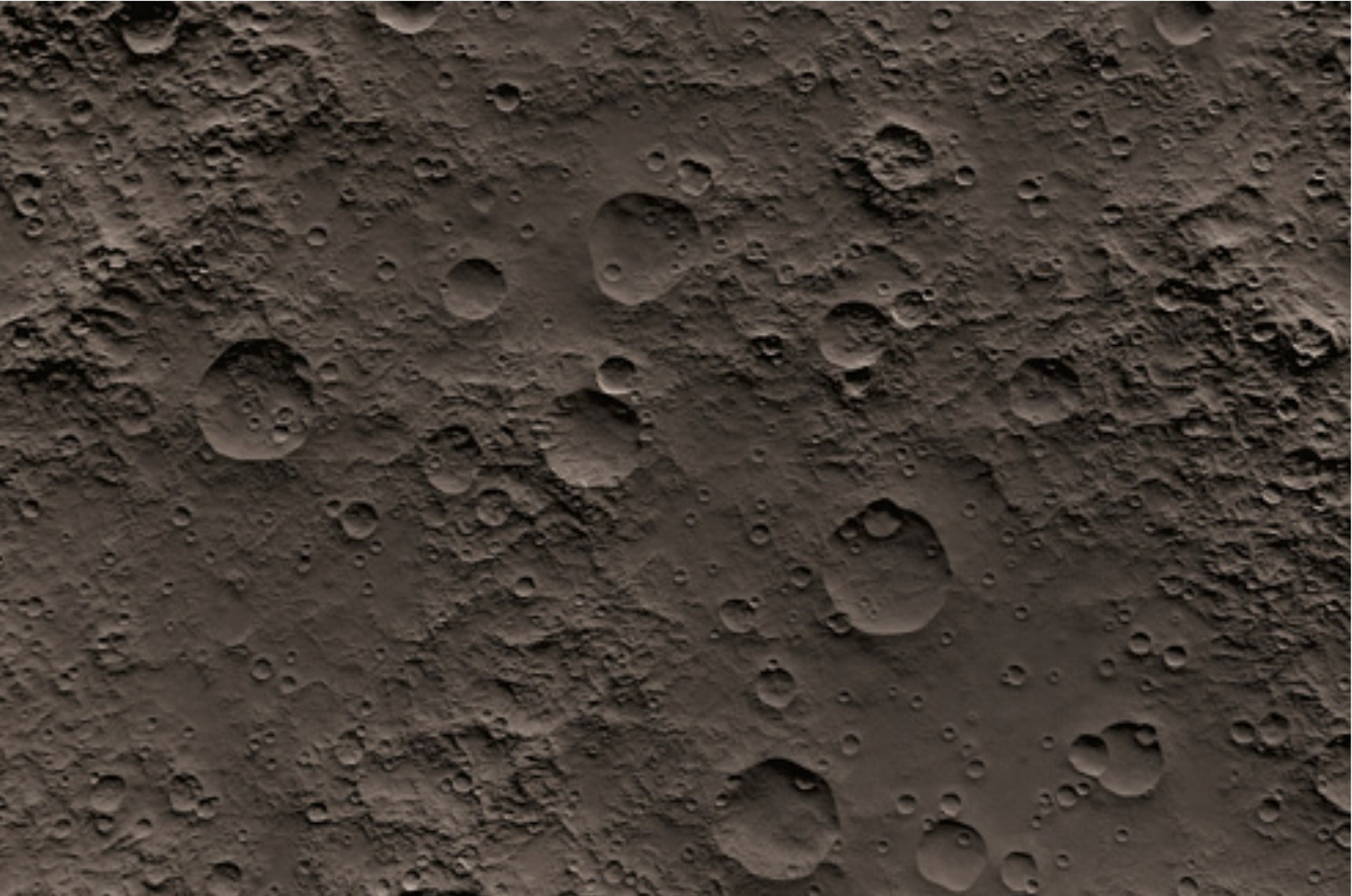

When rock and regolith samples first arrived back on Earth during the Apollo missions, they were carefully guarded for fear of contamination — the threat of Earth-based germs affecting the samples and vice-versa. Since the lunar samples were limited in size and highly valuable researchers created regolith simulants that mimicked the chemical and physical composition of the lunar samples.

Due to the nature of lunar regolith particles, it came as a surprise that the plants germinated at all. “Lunar regolith is sharp and angular,” Ferl explained to Astronomy. “There was no reason to think that plants would embrace it whatsoever.”

Surviving, Not Thriving

Compared to the control group, the seeds grown in the lunar regolith were stunted and stressed. They also engaged different genes than their terrestrial counterparts to adapt to their hostile new environment.

The University of Florida team only had 12 grams of lunar regolith to use in their experiment after applying three times for access to NASA to use actual lunar samples. Fortunately, the study yielded a treasure trove of results.

Paul reported that all the plants looked similar until day six of the 20-day growth period. It was then that many of the lunar-based plants began to grow slower, reveal stunted roots, and take on a reddish coloring. Those in regolith from Apollo 17 were the least affected, suggesting that less mature lunar soil is a better substrate for sustained plant growth.

Beyond demonstrating that plants can grow in lunar regolith, the study gave insight into how Earth plants might affect other worlds. While soil impacts the life of a plant, a plant enacts changes upon the soil. Indeed soil or “dirt” is actually a term used to describe the mixture of rock particles (regolith) and organic matter created by plants and microorganisms. Since the Moon is sterile the stuff we’re tempted to call lunar “soil” is actually lunar “regolith”.

Now that a first trial has shown that Earth plants will grow in regolith from the Moon, other regolith samples from the Moon or Mars can now be more closely studied for chemical signatures indicating plants once grew in them. These “biosignatures” are the chemical traces that Astrobiologists strive to observe when they look for evidence of life – past or present – on other worlds.

From the Lab to the Lunar Surface

Paul, Ferl, and Elardo conducted their study in an environment meant to resemble a base on the Moon, since growing something in direct contact with the actual lunar surface where there’s no air, water, and the temperature swings from 200 – -200 F is not possible. But growing plants within controlled habitat on the Moon is not only feasible – it is highly desirable.

The Florida team grew Arabidopsis thaliana in ventilated terrarium boxes akin to those that may be deployed on upcoming Artemis missions within the Lunar Gateway mini-space station orbiting near the Moon.

Although more research is necessary, the study revealed the possibility that astronauts can feed themselves for lengthy periods using resources found in situ. Doing so would free up more space on their ships to bring along life-preserving materials and habitat-building tools because they would not have to haul tons of “dirt” with them. You’d start with lunar regolith and over time, as generations of plants were grown, develop actual lunar “soil” that can be reused.

According to NASA administrator Bill Nelson, the study’s results have even wider implications. He called it an example of “how NASA is working to unlock agricultural innovations that could help us understand how plants might overcome stressful conditions in food-scarce areas here on Earth.”

Other agricultural experiments also point to a bright future for our space-bound species. Onboard the International Space Station, astronauts recently grew multiple batches of chiles (and then used them for taco night). Innovative vertical farming techniques are presenting new possibilities for the global food supply in metropolitan areas on Earth. And other research has shown that alfalfa sprouts will make a good fertilizer for terraforming Mars.

Plants can be part of a life support system by recycling air and water and many environmental contaminants. Plants can also be used as part of the food supply for human crews. Also, as has been demonstrated at several Antarctic research stations, the growing chambers themselves also offer a place for humans to relax and escape the often harsh, drab confines of their remote research location.

One of the first things human settlers have done – whether it was Europeans crossing the Atlantic and arriving in North America or Polynesians expanding across the Pacific to settle a myriad of islands, planting crops was one of the first orders of business upon arrival at their destination. We’ll be continuing that tradition as we expand outward from Earth.